Colonial feminism–one of colonialism’s earliest obsessions and justifications–reared its head in the nineteenth century. It achieves widespread resonance in the Western imagination because of the West’s inherent sense of its cultural and intellectual superiority–what Edward W. Said labeled “Orientalism.” It was one of several justifications for an empire to help veil its instrumental and political goals and violent and repressive truths.

The literature that looks at the role of women and imperialism is vast, but a few works worth mentioning here include Saba Mahmood, Religious Difference In A Secular Age, Princeton University Press, 2016; Sara Faris, In The Name of Women’s Rights, Duke University Press, 2017; Malek Alloula, The Colonial Harem, University of Minnesota Press, 1986; Jasbir Puar, Terrorist Assemblages: Homo–nationalism in Queer Times, Duke University Press, 2017; Inderpal Grewal, Transnational America; Feminisms, Diasporas, Neoliberalisms, Duke University Press, 2005; Amy Kaplan, The Anarchy of Empire In The Making of US Culture, Harvard University Press, 2005; Ann Laura Stoler, Race And Education of Desire; Foucault’s History of Sexuality and the Colonial Order of Things, Duke University Press, 1995; Sarah Graham-Brown, Images of Women: The Portrayal of Women in Photography of the Middle East, 1860-1950, Quartet, 1988; Billie Melman, Women’s Orients: English Women and the Middle East, 1718–1918, Palgrave–MacMillan, 1992; Marnia Larzeg, Torture and the Twilight of Empire: From Algiers to Baghdad, Princeton University Press, 2007; Joseph Massad, Islam in Liberalism, University of Chicago Press, 2015; Mehammed Amadeus Mac, Sexagon: Muslims, France, and the Sexualization of National Culture, Fordham University Press, 2017; Leila Ahmed, Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate, Yale University Press, 1993; Adi Kuntsman, Esperanza Miyake (Eds), Out of Place: Interrogating Silences in Queerness/Raciality, Raw Nerve Books, 2008.

The theft of Muslim/Arab women’s bodies and exploitation as justifications for colonial conquest has a long pedigree. We find these bodies utilized by the British in India, the French in Algeria, colonial administrations in Egypt, and elsewhere. [Leila Ahmed, Women and Gender in Islam, Yale University Press, 1992; Marnia Lazreg, The Eloquence of Silence: Algerian Women in Question, Routledge, 1994; Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can The Subaltern Speak,” In Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman (Eds), Colonial Discourses and Post-Colonial Theory, Harvester, 1993:93]. Modern-day US imperialism’s exploitation of Muslim/Arab women’s bodies is undoubtedly no exception. [Saadia Toor, “Gender, Sexuality, and Islam under the Shadow of Empire,” The Scholar & Feminist Online, Issue 9:3, Summer 2011; Deepa Kumar, Islamophobia and the Politics of Empire, Haymarket Books, 2012]. It continues a Western tradition of using progressive and liberal discourses to justify and veil colonial wars, occupations, resource theft, and white settler communities. [Sarah Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness, Duke University Press, 2010:123–133].

As Pramod K. Nayar has argued, Europe’s colonial civilizing mission dovetailed different forms of domination and control. It relied on rhetorics of “reform, rescue, and more and material progress.” Women were essential to the project. “The rescue of allegedly subjugated native women,” Nayar points out, “treated social reform of the barbaric races as a bounden duty and saw the moral progress of the natives as intimately connected to their material progress.” [Pramod K. Nayar, Colonial Voices: The Discourses of Empire, Wiley & Sons, 2012].

Elsewhere, the French explained their colonial practices and the brutal violence and expropriation of bodies and resources they entailed through humanitarian discourses. Albert Sarraut, the French colonial minister in the Congo from 1920 to 1924, had justified constructing the Congo-Océan railway as serving ‘human solidarity and not as the straightforward colonial exploitation project that it was. “It is for the good of everyone that we act,” Sarraut argued in a speech in 1923, “and primarily, for the good even of those that appear dispossessed.” [J. P. Daughton, “The ‘Pacha Affair’ Reconsidered: Violence and Colonial Rule in Interwar French Equatorial Africa,” The Journal of Modern History #91, September, 2019:493–524].

The Arab/Muslim woman has long been one of the main sites for practicing progressive imperialism, drawing the concern of Western patriarchy and compelling its men to act to “save them.” Women’s bodies have been stolen in the service of US imperial wars, and this theft is evidenced best and most unapologetically on the pages of mainstream publications.

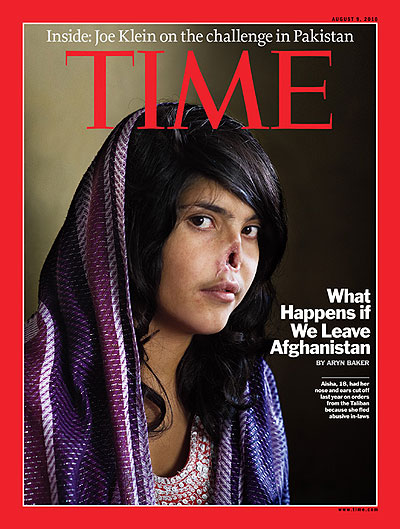

In 2010, as doubts and questions were being raised about the continuing US military occupation of Afghanistan, Time magazine published a cover portrait of a young Afghan woman whose face had been brutally mutilated and was left with a “jagged bridge of scarred flesh and bone” where her husband had cut off her nose. “We do not run this story,” Richard Stengel, the then editor of the magazine, disingenuously explained, “or show this image either in support of the US war effort or in opposition to it. We do it to illuminate what is actually happening on the ground.” [Richard Stengel, “The Plight of Afghan Women: A Disturbing Picture,” Time, July 29, 2010].

Time magazine reduced Aisha’s personal history, life, memories, ambitions, desires, relations, social connections, and culture, making her useful in US imperialism’s civilizational narrative. “Aisha posed for the picture,” Stengel continued, “and says she wants the world to see the effect a Taliban resurgence would have on the women of Afghanistan, many of whom have flourished in the past few years.” Manufacturing a sovereign subject who stands outside power, interests, influence, and coercion, Time offered us a ready-made woman “empowered” by US power. Liberal, “woke” politics was weaponized, and women’s bodies became ammunition.

[Aside: The story was written by Aryn Baker, Time magazine’s correspondent in Afghanistan and Pakistan. It was later learned that she was married to Tamim Samee, an Afghan-American IT entrepreneur, who was on the board of an Afghan government minister’s $100 million project advocating foreign investment in Afghanistan, and “has run two companies, Digistan and Ora-Tech, that have solicited and won development contracts with the assistance of the international military, including private sector infrastructure projects favored by U.S.-backed leader Hamid Karzai.” That is, a journalist writing for a magazine advocating for the need for the US to continue the war in Afghanistan is married to a man who stands to benefit financially from the US continuing the war in Afghanistan. [Jason Linkins, “Aryn Baker, Time Magazine’s Afghanistan Reporter, Failed To Disclose Conflict Of Interest: NY Observer,” HuffPost, May 25, 2011.]

Sara Ahmed points out how progressive imperialism and its discourses remain a form of domination and power, ensuring that the European/Western subjects “remain in a position of the one who is active/heroic/giving to the others. If the others do not receive this gift happily, they become ungrateful or mean.” [Sara Ahmed, “Progressive Racism,” feministkilljoys, May 30, 2016]. Stengel speaks for Aisha and places her where his progressive imperialism needs to put her: as an object of Western salvation and protection. Her agency, voice, individuality, and visibility are entirely determined and defined by her place and possibility by her role in a story she did not write, nor can she change. She is visible for as long as she is valuable.

It wasn’t a coincidence that Time magazine published this cover story just days before Wikileaks released the Afghan War Diaries, which documented extensive evidence of war crimes, military corruption, and the overall failure of the war. [Wikileaks Afghan War Diary online here: https://wardiary.wikileaks.org/search/?sort=date&release=Afghanistan (last accessed December 2023)]. Aisha is trapped inside the cage of war. She will cease existing should she dare to veer from the script.

It is what happened to Malalai Joya, An Afghan woman who lost her status as the right kind of Afghan when she started to speak out against the American occupation of Afghanistan, the violence and suffering it was inflicting on the people, and the criminality of the American puppet regime under the warlords and war criminals of the Northern Alliance. [Malalai Joya, Raising My Voice, Rider Books, 2010:201.]

In a write-up about her in Time magazine, Ayaan Hirsi Ali–a Muslim woman who had discovered the gold at the end of the neoconservative rainbow–patronizingly hoped that Joya “comes to see the US and NATO forces in her country as her allies. She must use her notoriety, her demonstrated wit, and her resilience to get the troops on her side instead of out of her country. The road to freedom is long and arduous and needs every hand.” [Ayaan Hirsi Ali, “The 2010 Time 100: Malalai Joya,” Time, April 29, 2010]. In Hirsi Ali’s words, we can hear how “secular redemptive politics” carries with it the “readiness to cause pain to those who are to be saved by being humanized.” [Talal Asad, Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity, Stanford University Press, 2003:62].

Today, many from the global south–including the media–are involved in this expropriation and capture of women’s bodies as the media, intellectuals, artists, writers, and feminists in “the global south have actively contributed to the articulation of new forms and new agents of imperialist feminism.” [Deepa Kumar, “Imperialist feminism and liberalism,” OpenDemocracy, November 6, 2014].

Nation-states have entered the game, particularly the most authoritarian, militarized, and repressive. Stories about ‘liberated’ and ‘modern’ women from repressive and dictatorial regimes who happen to be US allies have received broad attention in mainstream US press. [Ishaan Tharoor, “U.A.E’s First Female F-16 pilot Leads Strikes Against Islamic State,” The Washington Post, September 28, 2014; “Saudi Arabia’s ban on women driving officially ends,” BBC News, June 24, 2018; Rosie Pepper, “The Saudi Crown Prince’s visit to the US will focus on changing his image rather than policy,” Business Insider, March 20, 2018; Ben Hubbard, “Saudi Crown Prince, in His Own Words: Women Are ‘Absolutely’ Equal,” New York Times, March 18, 2018;]. The woman is weaponized, and she is safely situated back in patriarchy, with her liberation and worth, meaning, and identity defined in terms set by it. As Lacan said, “la femme n’existe pas.”

Using women as “window dressing” is a lesson that was quickly learned and put to use, and when it came to US allies, these stories were eagerly published. The use of women is not about the women. It isn’t in the service of a liberal ideal, either. It is always about imperialism and producing among the citizens of imperial metropolises a conviction that what “redeems [imperial violence] is the idea only. An idea at the back of it; not a sentimental pretense but an idea; and an unselfish belief in the idea—something you can set up, bow down before, and offer a sacrifice to.” [Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness, Broadview Literary Texts, 2003:19].

But we are not done talking about the uses of the Muslim woman and her exploitation for defending white supremacy and US imperial interests. I will discuss further aspects of this kidnapping in the next chapter.

US imperialism is no ordinary imperialism. It is a “hegemonic imperialism, exercising to a maximum degree a rationalized violence taken to a higher level than ever before through fire and sword, but also through the attempt to control hearts and minds.” It is also a far more complex and multi-faceted phenomenon, camouflaging its intentions and practices in sophisticated bureaucratic, economic, and diplomatic ways. Imperialism can be challenging to recognize because it appears in many different forms.

It can appear as economic warfare, humanitarian interventions, compliant dictators, sanctions, arming of proxy militia, CIA-backed coups, digital sabotage, surveillance, and sophisticated psych-ops techniques to bend public opinion to maintain its domination. Its schemes are chameleon-like, camouflaging themselves behind humanitarian, human rights, cultural and moral discourses. Imperialism can be seductive, convincing many that its trajectory is modernity, progress, and success. It can even convince the “descendants of the colonized” to collaborate in the repression and dispossession of their people and consider it progress.

And it is made invisible by a US media seduced by the myths of US exceptionalism and a sense of manifest right to dominate. It is laundered by a compliant, ideologically driven media machine that cleanses its devastating and murderous consequences and recreates reality as conducive and awaiting its attentions. .