A National Geographic Magazine article titled “How Muslims, Often Misunderstood, Are Thriving in America” offers us a carefully curated view of the “good Muslim” in America.

We are introduced to “Muslim” subjects that have been carefully curated. We meet a former Marine sergeant, a pastry chef, an Elvis impersonator, a Sufi practising a “peaceful” Islam, a professional football player, a radio producer, a journalism student, a police officer, a Palestinian entrepreneur, and more. “Muslim communities in America are thriving,” we are told, because of their successful integration into America’s commercial, pop, and consumer culture. “Mattel™ has even debuted a Muslim Barbie™,” the writer gushes, suggesting that there could not be a more significant indicator of Muslim “integration” in America than their acceptance into its consumer culture.

[Aside: Coincidently, Inderpal Grewal has an interesting discussion about introducing Barbie dolls into India and how Mattel, the company that produces Barbie dolls, “uses multiculturalism to commodify race and gender difference. Relying on the work of anthropologists…on the anthropometry of Barbie…showed that the African American Barbie had almost the same body as the “regular” Barbie, except that its back was angled differently…[For] Mattel, the difference was merely a matter of costume.” But more importantly, she points out how “Barbie in a sari became meaningful in new ways. It enabled South Asian immigrants in the US to give their children what they wanted…but with a difference that recalled their “traditional” culture–and important aspect of the formation of diasporic ethnic identity in a highly racialised America.” Grewal’s analysis offers a consumer/capitalist frame for understanding the development of transnational and diasporic identities among “Muslim” immigrants to America. From Inderpal Grewal, Transnational American: Feminisms, Diasporas, Neoliberalisms, Duke University Press, 2005:107–111].

The people we meet confirm American generosity, diversity, and “melting-pot” mythologies. “I feel I live here with more freedom and courage than anywhere else in the world,” says Elham Karajah, a nurse. Fatima Kebe, an industrial engineer from Dearborn, Michigan, says, “I am thankful to live in a country that supports freedom of religion.” Then there is the man from Gaza, “born into a poor family,” who came to America, met a white American woman, fell in love, got an education, got himself a large house with a pool, and became an entrepreneur. “I wanted to show that not all Muslims are terrorists,” we hear a Palestinian-American man say, revealing how people internalise settler logic, recasting resistance to settler colonial crimes as “terrorism.”

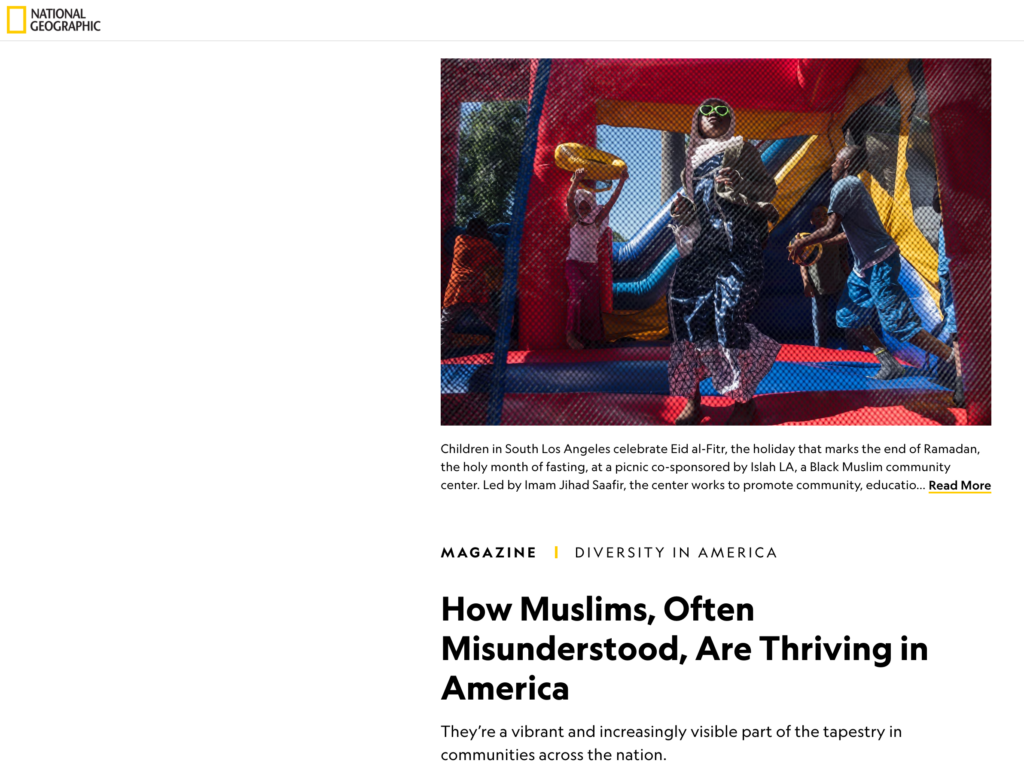

The photographs accompanying the article are bright, colourful, and suitably diverse, showing “Muslims” in prayer, play, parenting, and professionalism. All the characters are either visibly identifiable by their “Muslimness” (hijabs, skill caps, prayers, rituals) or identifiable by their non-Muslimness/secularism as they are shown taking part in “American” traditions of pizza, hip hop, parties, fashion shoots and even, joining the US armed forces. We see religious devotion, professional determination, and mild debauchery, covering what the magazine believes is the acceptable spectrum of Muslim lives in the USA. We can see the depiction of differences in the photographs that illustrate the article. The photographer’s eye uses the same social, cultural, religious, and ethnic markers to identify “Muslims” as the US surveillance state–hijabs, skull caps, mosques, religious rituals, community centres, and neighbourhoods. That is, she operates with a reductive and limited definition of what qualifies as a photographable “Muslim” subject, prioritising those that most stand out for their identifiable “Muslimness.” She finds what she is looking for, i.e., the difference. She does this not only when visiting the mosques or prayer groups but also when she photographs the “secular,” who is shown in circumstances and situations the reader can easily associate with secular American culture, hence not “Muslim” culture. She offers “Muslims” becoming “American,” which is the underlying theme of the article, by showing us an Elvis impersonator, a US marine, a very typical firefighter, and a candidate for governor—trajectories of “integration,” which are otherwise equally trajectories of disappearance.

The article acknowledges that Muslims “in America are living in a climate of hostility”. Still, it quickly deflects any further discussion by blaming “anti-Muslim rhetoric from conservative commentators and politicians, including the president [Trump].” This is disingenuous at best and wrong at worst. Islamophobia in a post-9/11 American has become a veritable industry, funded and financed by powerful groups spewing out racist and reductive ideas about Islam, Muslims, and Arabs [Nathan Lean, The Islamophobia Industry: How the Right Manufactures Fear of Muslims, Pluto Press, 2012]. But the conservatives are not the only ones to blame. US media, liberal and conservative, has peddled the worst generalisations and stereotypes about Arabs, Muslims, and Islam. Writing in the late 1970s, Edward Said pointed out that US media’s simplistic representations of Muslims and Arabs as terrorists, dictators, and oil tycoons were “thus contributing to the creation of widely held negative stereotypes that depicted Islam as ‘medieval and dangerous,’ as well as hostile and threatening to ‘us’” [Edward W. Said, Covering Islam: How The Media and The Experts Determine How We See The Rest of the World, Vintage Books, 1997].

Muslims and Islam have predominantly been presented through the lens of terrorism and violence. A recent study revealed that nearly 61% of all articles published by the New York Times about Islam or Muslims are about terrorism, violent conflict, or war. At The Wall Street Journal, nearly 73% of all articles published about Islam or Muslims are about these same themes [Malia Nora Politzer and Antonia Olmos Alcaraz, “Covert Islamophobia: An Analysis of The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal Headlines Before and After Charlie Hebdo,” Comunicación y Sociedad, 2020, e7601, pp. 1-24].

Despite the heavy-handed and syrupy image of American social perfection, the ghosts of America’s imperial geography–its war zones, its compliant dictatorships, its settler-colonial allies–haunt the spaces between the words. We see and read about individuals from Gaza, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia, yet we read nothing about them and their reasons for “arriving” in the US. Their histories and memories are carefully excised and begin only after arriving in America and after their “success.” The silences–about war crimes, about millions dead and displaced, about occupation, torture, renditions, drone killings, indefinite detentions, surveillance, deportations, and entrapment–and how these experiences inform and define the life of the diverse, complex, varied, and vastly different Muslim communities in America in American, are never considered. The writer instead finds the “Muslims” who stand outside history and politics and become “individuals” cleansed of political and ethical concerns, trapped within their religion as identity and the USA as their geography. At one point, the writer compares her family story to a man from Gaza. Learning that he is married to Heidi, a white American woman, and has two daughters and a son, she reflects.

This family reminds me of my own. My father, from Lebanon originally, also came to the United States for an education and a better future, as Ajrami did. My mother was a Unitarian Universalist, like Heidi, and she met her future husband in college and converted. My parents have raised five ambiguously tan American Muslim kids.

But she may share something far more than that. The man from Gaza is fleeing a US imperial geography. He has had to seek “a better future” because of the chaos, destruction, and violence created by Israel. This nation sits at the heart of the US imperial project in the Middle East and oversees an illegal, brutal occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. It is an occupation aided, abetted, and funded by the US. Lebanon, too, only stands in this US imperial geography. Did the writer’s father flee the US geography of war, too? Lebanon was the site of the first overt US military action in the Middle East. In 1958, US Marines poured out of their landing crafts onto the sands of Khalde Beach. “Operation Beirut” resulted from a panic created in US political corridors by Arab nationalism, a force they were determined to destroy. This was the groundwork for further US interventions in the region, including that in the second Lebanese civil war of 1975-1990 [Bruce Riedel, Beirut 1958: How America’s Wars in the Middle East Began, Brookings Institution Press, 2019].

In the National Geographic imagination, individuals arrive in the USA of their own free will, “better themselves,” and build a “better life.” They face challenges but overcome them through individual struggle and optimism. History and memory begin only upon their arrival on the shores of the USA, and they are directed to speak of themselves only as individuals and only as “Muslims” working to “fit into” America. But this is a fantasy. Projecting your “identity” in reaction to a society that discriminates against you based on that same “identity” is an act of capitulation to the discourse of power. It is a surrender to the terms of “recognition” and acknowledgement defined by authority.

The “good Muslim” is a surrender to US xenophobia