In 2015, MSNBC, in collaboration with Magnum Photos, published an online multi-media series called Continental Driftı. This was at the height of the so-called “European migrant crisis,” as tens of thousands of people fled the chaos and deadly aftermaths of American and European wars in the Middle East. Written by Tony Doukopil and Amanda Sakuma, the entire piece–beautifully designed and powerfully photographed by several Magnum photographers–conveniently conflated the thousands driven across the waters of the Mediterranean because of Western wars with those forced across the deserts of Africa because of unjust and exploitative trade agreements signed between Europe and other nations.

[Please note: This essay is no longer available on the MSNBC website, where it first appeared in 2015. It can be found via The Way Back Machine.

The main essay is here: https://web.archive.org/web/20160304220313/http://www.msnbc.com/specials/migrant-crisis/mediterranean and https://web.archive.org/web/20160303173423/https://www.msnbc.com/MigrantCrisis.

The Libyan portion of this piece, written by Amanda Sakuma, can be found here: https://web.archive.org/web/20160517151940/https://www.msnbc.com/specials/migrant-crisis/libya.

Her second essay, one on the Mexican and Central American migration crisis, is archived online here: https://web.archive.org/web/20170501225348/http://www.msnbc.com/specials/migrant-crisis/mexico].

I address three parts of this series in this essay.]

At the height of one of the biggest stories in Western media, a journalist spends thousands of words addressing the issue of migrants but assiduously and determinedly avoids touching on the causes and reasons for the creation of the crisis. He spends thousands of words avoiding using any word that may reveal the horrors that the West has spread and the realities of the millions of lives that it has destroyed. This essay, cleverly crafted and beautifully photographed, becomes an exercise in obfuscation and erasure.

Tony Doukopil, in the chapter called “The Mediterranean Route,” explicitly identifies regions of recent Western militarism as a significant source of refugees; he assiduously avoided speaking about Western wars as the cause and reason for people fleeing.

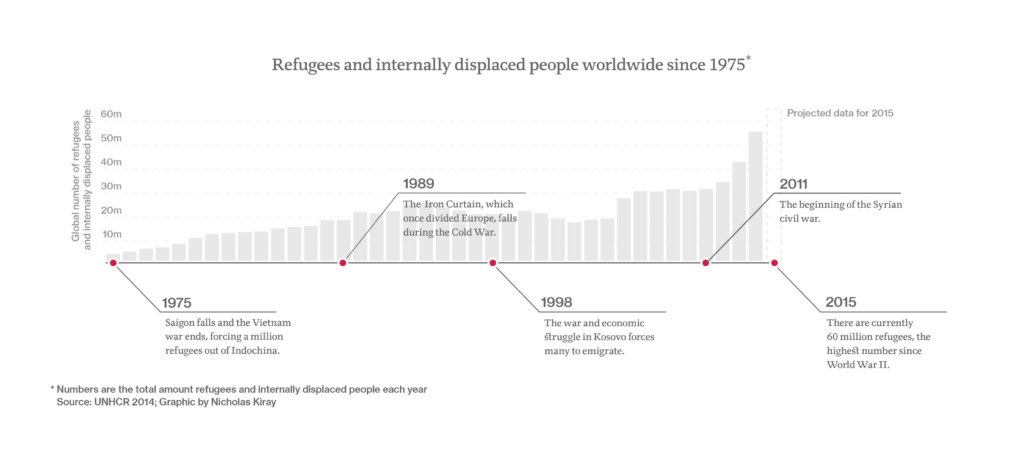

A bizarrely and unconscionably evasive graphic showing the number of refugees by year, only four major events are highlighted as relevant: the 1975 fall of Saigon, the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall, the 1998 war in Kosovo, and the 2011 start of the Syrian “civil war.” Apparently, between 1998 and 2011, a thirteen-year gap where we say America and its Western allies attacked and invaded Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya and began massive campaigns of war in regions of Pakistan, Somalia, Yemen, and, of course, Syria was not worthy of highlighting. The entire graphic erases Western aggression as a milestone worth highlighting–the 2001 illegal invasion of Afghanistan, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the 2011 USA/NATO attack on Libya, and so on, do not count as significant enough to note.

Doukopil’s only reference to the recent displacement of millions from Western geographies of war is made in a somewhat evasive and misleading paragraph that states:

Most Americans are familiar with the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan and possibly Syria’s foul and bloody civil war. But what about the Yemeni Civil War? Or the clash between rival governments in Libya? Or the hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians forcibly displaced within their borders?

Note how all these conflicts are written as if they had nothing to do with the aftermath of US direct or indirect political and military interference. So desperate is he to avoid pointing the finger at the single most significant political power destabilizing the region, killing hundreds of thousands, dropping bombs, running torture centers, carrying out invasions, and supporting occupations that he has to jump through time loops in ways that time travels would envy. For example, when speaking about the reasons for the millions drifting onto the shores of Greece and Italy, Doupkobil claims that:

They turn away from ISIS in Iraq, civil war in Syria, and religious violence throughout the Middle East and North Africa. What they face in exchange is a wall of public anxiety, virulent populism, and the threat of closed borders for thousands of miles.

Civil war, religious violence, populism, and ISIS. It is as simple as that if you have the superpower to control time and manipulate histories. Western journalists do. Instead, we are told, using some of the worst racist cliches about regions of the Middle East, that the refugees:

Instead of ducking dictators and kings, they run from terrorists and warlords.

We see how, in Doupkobil’s world, colonial, imperial, and political histories vanish and how the chaos the West creates is white-washed by journalists as “civil war” or blamed on the demons like ISIS that the US practices, policies, invasions, and violence give birth to. The chaos unleashed across the region, the millions killed and displaced now roaming in desperation, become victims of “religious violence,” or those of ISIS. But the West, its barbarism, and policies and practices are never center stage. American and Western innocence, a form of Western exceptionalism, is religiously preserved in such narratives and reportage projects that invest heavily in aesthetics and spectacle yet remain shallow and evasive in providing understanding and truths.

Doupkobil has to go further to sustain these obfuscations because he has to speak about causes. For this, he constructs, however, inadvertently, the specter of “dangerous Muslims” now roaming the graceful and peaceful landscapes of “innocent” Europe. The article discusses terror attacks in European capitals without once mentioning that European states have been willing and excited collaborators in America’s military adventures and occupations, torture programs, rendition schemes, and targeting of dissenters and whistleblowers. They are complicit and willing belligerents waging war across the Middle East.

European countries like Austria, Belgium, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Indonesia Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Macedonia, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom were “actively involved in assisting in the capture and transport of detainees; permitting the use of domestic airspace and airports for secret flights transporting detainees; providing intelligence leading to the secret detention and extraordinary rendition of individuals; and interrogating individuals who were secretly being held in the custody of other governments.” [Amrit Singh, “Globalising Torture: CIA Secret Detention and Extraordinary Renditions,” Open Society Justice Initiative Report, 2013].

For millions, they are the very enemy that destroyed their societies, communities, and lives. But this cannot be acknowledged. For Western journalism, the chaos and madness of the “Other over there” has nothing to do with us over “here.” Violence in our peaceful and innocent capital cities has no relation to the mass death and chaos Western societies have funded, armed, and diplomatically enabled.

Amanda Sakuma, another correspondent featured on this MSNBC online feature, repeats the discourses of European politicians and pundits, editorials, and commentators. She merely regurgitates the parrots of the very right-wing rhetoric and a-historical narratives that are used to fuel hatred and violence against migrants. In her contribution, which focuses on the situation in Libya, she writes:

To tell the story of Libya’s escalating migration crisis, one must weave together the threads of instability left behind by a toppled dictator, Muammar Gaddafi, and the power vacuum filled by rivaling factions vying to take his place. The chaos allowed smuggling networks to thrive, suddenly opening up a lucrative market designed to profit off trading humans like other goods and commodities.

But who “toppled” Gaddafi? And how did his murder at the hands of NATO/American-supported militia become rewritten as a toppling in the first place? His assassination–one that led Hilary Clinton, then the Secretary of State in the Obama Administration, to ghoulishly boast that “We came. We saw. He Died”–is written away as a “fall from power and subsequent death in 2011,” as if it all happened by natural causes. [See Clinton’s statement here: https://youtu.be/mlz3-OzcExI?si=Z7uCRJX9CdYLAzmQ].

Sakuma speaks of the chaos created in Libya after the violent removal of Gaddafi, recognizing the violence and insufferable chaos that enveloped the country in the aftermath. But she never tells us why and how this happened and erases our fingerprints over this disaster. She overtly lies and argues that:

Conditions inside Libya have deteriorated since the citizen uprising (emphasis mine) against Gaddafi and the government’s collapse in 2014. Armed conflict between two rival factions has engulfed the country as they fight for legitimacy. The chaos has caused a massive displacement of hundreds of thousands of Libyans who are left now without work or a place to call home.

Gaddafi wasn’t toppled as a result of a “citizen uprising.” Sakuma knows this well. Even mainstream press, by 2015, when she penned this piece, had gotten over its previously propagandistic framing of the attack on Libya as a “citizen uprising.” By 2015, no one would have had the audacity to make this false claim. But Sakuma and the editors at MSNBC, in collaboration with indifferent or unconcerned Magnum photographers, did make this claim.

It was the language of state propaganda, now repeated unthinkingly by a writer at a major news outlet. The fall of Gaddafi came as a result of an American-supported NATO assault on a sovereign nation, one that “violates international law, shows callous disregard for the innocent, and prosecutes a war approved by no international body, declared by no national parliament and sanctioned by no moral code.” [Benjamin Barber, “Libya: This is Nato’s Dirty War,” The Guardian, May 2, 2011]. The illegality of this attack, one that is repeatedly misrepresented as a “citizen uprising,” was such that even the New York Times, a publication that generally acts as a cheerleader for American wars, was forced to question President Obama’s decision to launch it. [Bruce Ackerman, “Legal Acrobatics, Illegal War,” New York Times, June 20, 2011].

The entire piece is a rewriting of Western imperial acts. It posits an innocent, calm, and tranquil Europe facing a wave of unwanted “others” streaming onto her shores, escaping chaos and violence that has little or nothing to do with Europe or America. The Other is the “threat,” forcing the West to ask tough questions, re-examine its ideas of self and society, and find ways to accept and accommodate those who “do not belong.”

Later in the same piece, Sakuma turns her attention to the Mexican and Central American migrant crisis, where caravans of migrants have been making their way across Mexico from countries like Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Sakuma is determined to pursue that classic strategy of Western journalism, speaking about the world through a lens that reifies political national boundaries as representative of genuine cultural separation and views acts of politics, economics, and society within these cartographic entities as isolated and independent of larger transnational forces such as international financial flows, multi-national corporate interests, imperial interventions, and cross-border cultural and personal histories.

She avoids bringing into her narrative the role the United States, the region’s hegemonic political and economic power, has played in fomenting this crisis. As Rebecca Gordon points out:

There is indeed a real crisis at the US-Mexico border. Hundreds of thousands of people…are arriving there seeking refuge from dangers that were, to a significant degree, created by and are now being intensified by the United States. [Rebecca Gordon, “The Current Migrant Crisis Was Created by US Foreign Policy, Not Trump.” The Nation, August 16, 2019]

[Aside: Other articles that point this out include Julian Border, “Fleeing a Hell the US Helped Create: Why Central Americans Journey North,” The Guardian, December 19, 2018; Mile Culpepper, “The Debt We Owe Central America,” Jacobin, November 2018, Stephen Kinzer, “Who’s responsible for the border crisis? The United States,” The Boston Globe, June 20, 2019.]

But Sakuma’s perspectives remain married to the official American line, rarely raising doubts about its public rhetoric and never looking past the neatly arranged national borders. “Congress agreed to invest $750 million,” she tells us, “to help prop up governments in the northern triangle. Another $40 million is dedicated to the international humanitarian groups that identify, vet, and process refugee candidates. Multiple US agencies assist in dismantling criminal “coyote” networks of human smugglers.”

She places the problems elsewhere, erases US trade practices and policies as a possible cause, and idealizes the USA’s actions as only humanitarian. But, the story of refugees arriving at the shores of Europe cannot be written simplistically, not if we are to account for real lives and real humans. As Rodney Benson put it when speaking about the role of economic policies like NAFTA and European trading agreements with African nations:

The complexity of the international causes of migration cannot be easily expressed as a melodrama. And mentioning them is ideologically sensitive: it suggests there could be something wrong about an economic system that most politicians—and journalists—take for granted. From the early 1970s to the mid-2000s—a time of neoliberal globalization and bloody conflicts in Central America manipulated by the US—immigration stories that mentioned international causes fell from 30% to 12% in leading US papers…Yet, too often, both French and US media fail to give the full picture on immigration. Their focus on emotion and on individual stories diverts attention from the fundamental political issues and leaves the way open for the simplistic “solutions” advocated by the far right. [Rodney Benson, “The Story Behind The Stories,” Le Monde Diplomatique, May 2015].

Time and again, we see photojournalists “speaking out” on behalf of the rights of illegal immigrants crossing into the USA from Mexico, but rarely do we find one who will connect the dots that read NAFTA, the devastation of the rural economies of Mexico, the creation of a vast labor pool or underpaid and surplus labor that this agreement created and that now serves the sweatshops there. We talk about “climate refugees” in Bangladesh but never make the connection between international fishery trade agreements, intentional water salinization, and the mass displacement of farmers to open up lands for shrimp farms. [Donatien Garnier, “Bangladesh’s Climate Refugees,” Le Monde Diplomatique, May 2007].

Pieces such as this create fixed ideas of belonging and un-belonging and do it by distorting histories of social, political, and economic entanglement and, of course, bloody histories of wars, invasions, and occupations. But these stories must be told, yet Western journalists and photojournalists continue to produce simplistic, comic book-like narratives. [Daniel Trilling, “How the Media Contributed to the Migrant Crisis,” The Guardian, August 1, 2019].

We may speak out against child labor but will not connect the economic policies of a state and their close relationship to structural adjustment programs (SAP) supported by the IMF and the World Bank that cut social welfare spending and force families to send their children to sweatshops. We may speak out against the environmental degradation of Tunisian farmlands but say nothing about the massive hotel developments that serve the holiday needs of millions of European tourists and that for swimming pools, entire rivers are re-directed, and whole villages are cleared.

Where do our stories go, and why do our lives get so quickly subsumed into simple, neat little narratives, denied the complexity, the depth, the plurality, the psychological and emotional multiplicity they possess?